GTMO Hearing: Does The Threat of Rape Make A Confession Involuntary?

By C. Dixon Osburn, Director, Law and Security program

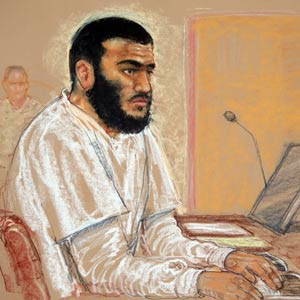

Does threatening a prisoner with rape and death, even implicitly, mean that a court should suppress admission of a crime because those statements lack voluntariness and reliability. That is the question raised today at a preliminary hearing in the case of Omar Khadr, being tried at the detention facility at Guantanamo Bay, Cuba.

Omar Khadr is the fifteen year old child soldier captured by American troops after a fire fight in Khost, Afghanistan in the summer of 2002. The United States claims that Mr. Khadr confessed to interrogators that he threw a grenade that killed an American soldier. Mr. Khadr claims that he did not. He claims that the admission was extracted from him through coercion. The government claims that it did not.

Today’s star witness was someone identified as Interrogator #1. He was the chief interrogator of Mr. Khadr at the Bagram Collection Point in Afghanistan. He testified that he interrogated Mr. Khadr twenty to twenty-five times. In a prior statement, he said he interrogated Mr. Khadr every day for four to six hours for what may have been at least 44 days, which would approximate 220 hours of interrogation.

Interrogator #1 testified that he interrogated Mr. Khadr the day after he was discharged from the hospital prison. Mr. Khadr, who was fifteen years old, was on a stretcher, greatly “fatigued” and “sedated,” according to #1, due to serious injuries he had received in the fight with American troops.

Mr. Khadr arrived at Bagram hospital on July 28, 2002, with a hole in his back the size of a Copenhagen chewing tobacco tin, a shredded cornea in his left eye which has left him blind, and a face peppered with shrapnel, which garnered Mr. Khadr the nickname “Buckshot Bob.” Prior to his release from the medical tents at Bagram, he underwent three major surgeries to repair his injuries.

Interrogator #1 questioned Mr. Khadr first on August 12, 2002, just 15 days after arriving at Bagram with the prognosis that he might not survive his injuries. Number One said that on that first day, and every day, he required Mr. Khadr to raise his head from the stretcher and look him in the eye during the questioning, which may have been very difficult for a young person having come recently out of surgery.

Number One said that the approved interrogation method he used that day and for the majority of the times he interrogated Khadr was “fear up.” The purpose of “fear up” interrogation is to scare the individual into cooperation. Methods may include screaming, cursing, turning over furniture in anger, all of which Number One confirmed he used.

Number One then said that he also used fictitious stories to instill fear in the young detainee. The lead defense counsel asked him to elaborate. He said that he had learned that Afghans were “terrified of rape and homosexuality.” So, he concocted a story about a prisoner like Mr. Khadr who chose not to cooperate with interrogators, was prosecuted and incarcerated in an American prison. Number One said that the convict was in the prison showers one day, alone, when “four big black men” and “neo-Nazis” entered the shower and raped him. He said that despite being in prison, these convicts were “patriotic Americans” who were very angry about 9/11. He said that the prison guards always try to help, but can’t be everywhere all the time and bad things can happen. He concluded the parable by telling Mr. Khadr that the young man in the story “may have died.”

It is not clear on which day of interrogations Interrogator One told the parable of American prisons, but he said that the story was targeted to Afghan citizens. He was under the impression that Khadr was Afghani only in the first few days of his detention. Khadr is a Canadian citizen.

The parable is disturbingly racist and homophobic. Bigotry alone, though, is not a basis to set aside a confession of murdering a soldier. Suggesting to a scared, impressionable fifteen year old who is on a stretcher just discharged from a hospital after three surgeries for life-threatening injuries, that he may be raped and die in an American prison unless he cooperates, though, may convince the military judge to suppress any statements made by Khadr. If the judge grants the motion to suppress the key evidence, the government will not have a case.

The chief prosecutor in the case claimed after the hearing that he remained “confident” in the case and that his confidence “continues to grow.” The lead defense attorney said that he thought that Interrogator One’s testimony about the implicit threat of rape and death may be tantamount to torture, and at the very least provided a strong basis to determine that the confession elicited from Mr. Khadr was not “unfettered,” “reliable” or “voluntary,” and should be suppressed.

What may determine the outcome of the decision about whether to allow or disallow the evidence of murder is how the military judge interprets the new rules governing this very hearing promulgated by the Department of Defense during the hearing. The Pentagon has issued multiple variations of the rules governing military commissions and they all have serious constitutional problems. The new set of rules does not appear to cure those constitutional defects, leaving any convictions in these military commissions vulnerable to reversal on appeal.

The military judge has promised to issue a series of rulings on Tuesday next week, and to set a calendar for the next evidentiary hearing. It is unclear how the judge will rule, but it is clear that Khadr case will be another difficult challenge to the continued viability of the military commissions.